Obvious reasons to be a locavores

There are many good reasons to buy local foods, to become a member of the “locavore” movement, whereby citizens are encourage to source more of their food from nearby farms.

- It is difficult to grow fresh, tasty tomatoes and transport them over long distances for sale. Most everyone knows that the best tomatoes are grown in our backyards or grown and sold locally.

- Sometimes food is cheaper at the farmers market. Rarely can local farmers compete with Walmart, but when sweet corn is ready for harvest it is hard to find corn of equal quality at a cheaper price than those found at farmers markets.

- Fresh foods are often more nutritious, so this means that the most nutritious foods can sometimes be found at farmers markets, food cooperatives, and the like.

Whenever consumers can find product delivering more value, whether it be the same product at a lower price or a higher quality product sold at a small premium, consumers should take advantage of the opportunity, and often this opportunity is found at farmers markets, community supported agriculture (CSA), food cooperatives, and other markets where local food is purchased. Producing “better” food, regardless of whether it is better because of quality or price, is just like a factory turning out cheaper products, or more valuable products. It increase the wealth produced in the region and therefore the wealth of the region overall.

The joy of local foods

There is another beneficial aspect of the local foods movement that took me longer to recognize. Local foods is not just a niche market. It isn’t just a form of food marketing. It is a food movement, what some would call a nascent food revolution. One objective of locavores is to convince you to cease mindless eating, to think deliberately about the varieties of food available to you, where they are grown, how they are grown, and how they impact the environment and your health. I first realized this when I read an article by Adam Nicolson in the July 2013 edition of National Geographic. This article (titled Hay, Beautiful) described the emergence of Transylvania out of the communist bloc and into the modern, capitalistic world. Most countries in a similar situation transitioned to fewer, bigger farms, where much of the farm product was exported to other regions and much of what people ate was imported.

This did not happen for Transylvania, at least not in regards to milk, and the reason has to do with the region’s love for its land and the beauty of its hay fields—festive, glamorous hay fields made beautiful by the polycultures of plants grown in the field, each giving off a different shape, color, and scent. A hay field operated under industrial agricultural techniques is a monoculture: one and only one form of grass of uniform height, uniform color, and uniform shape. Certainly, that industrial hay field is more productive and, when used as cattle field, reduces the price of milk. Transylvania's love for its traditional hay field is so strong that a local market for milk developed, where consumers gladly pay the higher price for local milk in return for preserving their landscape and traditions.(B1,D1,N1,W1)

Because it is real whole milk ... a piece of the past which their city life has left behind.

—A Transylvanian’s answer as to why cities were paying higher prices for local milk. Nicolson, Adam. July 2013. “Hay. Beautiful.” National Geographic. Page 124.

Locavores have encouraged us take an interest in what could be grown in our region, and allowed us to actually meet the farmers that grow our foods. We can ask questions about their farm. See pictures of their farm. Many actually visit the farm itself.

Yes we can. The government may or may not do certain things with agricultural policy and health policy, but we can all garden.

— Roberts, Wayne. 2013. “Lecture 8C: Why the Food Movement is Spreading.” An Introduction to the U.S. Food System: Perspectives from Public Health. Coursera.com.

The locavore movement is as much about education as it is food marketing. Education is why Will Allen constructed greenhouses in “food deserts” (usually poorer urban neighborhoods, where little fresh, unprocessed food can be found) so that people in poor urban areas can learn about how food is grown, and taste fresh organic vegetables straight off the living plant. Other locavores are constructing vegetable gardens at schools, and hosting field trips so kids can become acquainted with food and agriculture at an early age.

Urban people’s interest in where their food comes from, and the quality of it—their worry about poisoned food, soil loss, toxicity, etc.—is a good thing ... If we stick only with the “local food” part of the movement, it’s not going to amount to much. We’ve got to simultaneously talk about cultural change and land use more generally.

—Mary, Berry, Executive Director of The Berry Center. October 3, 2013. “Mary Berry is Fomenting an Agrarian Revolution.” Spotlight. Moyers & Company. Accessed October 6, 2013 at http://billmoyers.com/2013/10/03/mary-berry-is-fomenting-an-agrarian-revolution/.

If you listen to the local foods advocates (for instance, the instructors of the MOOC class An Introduction to the U.S. Food System offered at Coursera), they do not just want individuals to take more control over the foods the eat, they want local communities to become more active in the U.S. food system. Specifically, they desire active citizens to help ensure that the foods their peers eat not only provides them nourishment but also provides public goods (of which a non-technical definition is: a good or component of a good that belongs not to the individual, but to the community). Examples of public goods includes soil conservation, environmental protection, food for the poor, and the like.

Such locavores are convinced that the current system of industrial agriculture fails to provide such public goods, and thus the only way the community to correct for this is for concerned citizens to assert more control over how food is raised, and they believe they can best do this if the farms are close. When people are surveyed about why they visit farmers markets, supporting sustainable and organic foods are some of the top reasons.(M1) Locavores thus want food to be grown near to them so that it is easier to force their vision of responsible agriculture onto the farmers (and it should be mentioned that often the citizens and the local farmers are the same people).

Externalities and panoramic-blurriness

All markets possess shortcomings in that, while they do a good job of providing goods that consumers want, there are often by-products of production that are not accounted for in markets. This is especially true in agriculture. These “things” not accounted for in markets economists called externalities.

When you go to buy bread at the grocery store you do not know whether the farmer did a good job of conserving soil or whether her fields suffered serious erosion. We care about soil erosion because it threatens the ability of future generations to feed themselves. When you buy pork you do not know how the farmer treated the animal, and around two-thirds of Americans really do want farmers to raise animals humanely. When you buy beef you may wonder about the carbon footprint of the meat, but few people really understand the relationship between beef production and global warming.

Many consumers have a sincere desire that their food be ethically produced. They don’t just care about the quality of the food as a source of nutrition, but how the production of the good impacts others. They try to take a panoramic portrait of their food to understand how their purchases affect the world, but the relationship between food and the world is complex, and however ardent our desire to take this portrait, it will always be blurry. Of course, just because the connection between the farm and the environment is unclear doesn’t mean we should ignore externalities. It just means that we have to pay careful attention to how we solve problems. In the presence of this panoramic-blurriness one could defer to experts in government agencies, who presumably have a less blurry view of the world, but there is an alternative, one that brings concerned citizens to farmers markets like the one here at Stillwater.

These individuals seek to overcome this panoramic-blurriness by getting to know the farmers who grow their food. If they want to know how they prevent erosion, they can just ask. Members of Community Supported Agriculture can actually see the farm where the food is produced, becoming an eyewitness of how the chickens are treated. If panoramic-blurriness results from viewing from a distance, the locavore movement asks us to bring the world into better focus by moving up-close to the farm, so close you can walk its fields and shake the hand of its farmer.

Sometimes, when you try and obtain a better focus on the world by studying the “big picture” more intensely, some of the ethical notions about how food and society interact turn out to be wrong, or more nuanced than initially thought. Take, for instance, the role between local foods, the local economy, and the carbon footprint of food.

Challening intuition: Locavores and the local-economic stimulus

If you asked economists the best way to wreck an economy quickly, they are likely to answer: erecting trade barriers with other regions. This is true regardless of whether we are talking about a nation’s economy or that of a small town. If this is the case, why do locavores argue that spending on local foods stimulates the local economy and increases the population’s wealth?

I admit, the idea of helping the local economy by buying local products is intuitive. After all, you are directly giving your dollar to someone in your immediate region, instead of to a grocery store that transfers the dollar to corporate headquarters at who-knows-where. This is why people often say buying local foods (or local anything) “keeps the dollars local”. It is not clear to me, logically, why we should love our neighbor anymore than someone in another state (or another country), but intuitively I understand that emotion.

Below is a quote taken from the documentary Locavore, an excellent film in many aspects but one that makes a poor economic argument. If Mr. English's claim about the local food multiplier was correct, doesn’t that suggest we are fools to not pass laws prohibiting food imports?

... and another advantage of buying from your local farmer is ... economists call it the multiplier effect. And that’s the number of times a dollar circulates in the community before it leaves the community. So when I go to the grocery store, somewhere between ten and fifteen percent of my dollar stays in the local community—the rest leaves, because it has to pay the truckers, it has to pay the agribusiness giants and the…warehouses. The money leaves the community. And if I spend the money with my local farmer, that guy, he pays his local property taxes, pays his school taxes (his kids go to the school), he goes and spends his money at the local feed store, the local hardware store—he spends the money here, in the community. It doesn’t leave the community. And, depending on who you talk with, that multiplier effect for agriculture—in an agricultural community—is five or six. That means it’s five times as effective as if you go to the supermarket and the money leaves the community. So [local food is] really economic development. —John English. 2012. Locavore: Local Diet Healthy Planet. Documentary. Director: Jay Canode. Studio: Createspace.

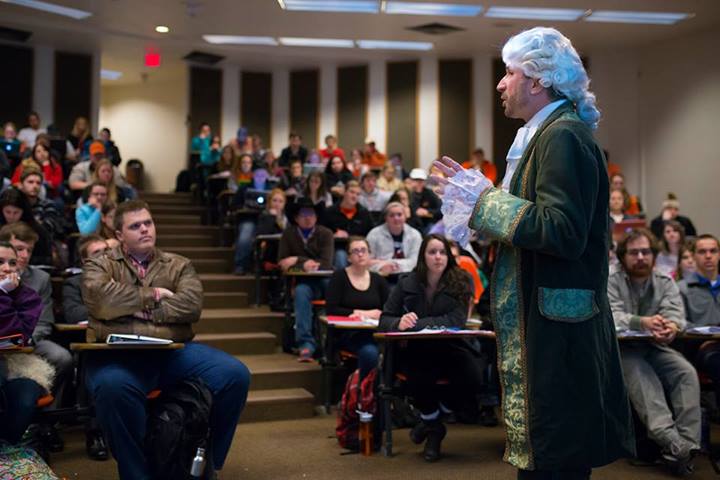

On the day I talk about the local foods movement in my Introduction to Agricultural Economics I come dressed as the philosopher David Hume (1711-1776), who I believe is the first modern economist. Back in the eighteenth century Hume wrote an essay titled On the Balance of Trade where he proved that, over time, exports from a region must equal imports. If two million dollars are spent importing goods every year to Stillwater, OK, then two million dollars are earned in Stillwater, OK by exporting goods. This proof has never been refuted by anyone, and I have studied the proof myself and believe it sound.

The proof is quite simple. Imagine if Stillwater decided to export more than they import. More dollars would be coming into Stillwater than leaving, and if this continues indefinitely Stillwater would eventually accumulate all the money in the world. Obviously that can’t happen, and it won‘, because as money accumulates in Stillwater it drives prices in Stillwater higher. These higher prices encourage Stillwater citizens to buy cheaper out-of-town, and when they do imports rise until imports equal exports.

Conversely, if Stillwater tries to import more than it exports then more dollars will be leaving Stillwater than entering. Continued indefinitely this would deplete Stillwater of all its dollars, but that won’t happen because as dollars become scarce in Stillwater prices fall, and then Stillwater businesses seek to sell out-of-town at higher prices, and as they do exports will rise until they equal imports.

No matter how you look at it, exports from a region must equal imports, so if Stillwater decides to replace some of its imports with local food they are simultaneously deciding to decrease exports. This will benefit certain Stillwater farmers and harm certain Stillwater exporters, but overall will most likely reduce the town’s overall wealth.

Hume’s essay also has the interesting implication that you also support your local community by increasing imports into the region by one dollar, because it will subsequently be matched by a dollar on local exports. By a German beer and you are indirectly buying something local as well.

I know this argument is hard to digest if one hasn’t studied economics for years, so I don’t expect you to be fully convinced. What I do hope is that I made you second-guess your natural intuition that purchasing local food benefits the local economy. If so, I have demonstrated that we must always be skeptical of intuitive notions, however obvious they may seem at first. Aristotle once remarked that, “It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it.” I don’t expect to have fully convinced you that the locavore movement will not make everyone wealthier, but I do hope that you now see the value of questioning the idea.

Figure 2—Dr. Norwood as David Hume

Challening intuition: Is local food better for the environment?

A decade ago many people did seem to make this argument, using the concept of food-miles. The idea was that transporting fuel requires fossil fuels, and fossil fuels emit carbon. The further distances food travels, then, the larger the carbon footprint of food.

The problem with the argument was panoramic-blurriness. Locavores tried to connect food with its impact on the world by taking into account the externality of carbon emissions, but the picture it painted was so blurred that locavores neglected to account for the amount of carbon emitted on a farm, and certainly, we care about total carbon emissions from our food, not just those involved with food transporation.

The argument didn’t withstand scrutiny for long. First, it simply isn’t a logical argument. People care about the total carbon footprint of food, not just the footprint from one aspect of food production like transportation. In a market economy agricultural production tends to take place where it is most efficient, and efficient production usually implies less greenhouse gases. Oklahoma, with its dry and pleasant climate is particularly well-suited for cattle production, and so an Oklahoma feedlot may emit less carbon than a feedlot located in Michigan. If you are a citizen of Michigan, then, it may be that the total carbon footprint of an Oklahoma steak may be smaller than a steak from a cow raised and slaughtered by your next-door neighbor.(L1)

It is also the case that industrial agriculture employees efficient transportation systems, such that transportation costs are a relatively small component of food costs. Driving a minivan to a farmers market to buy a few heads of lettuce is not efficient. This means that hving a truck of carrot crossing three states may emit relatively few carbon emissions per carrot, whereas soccer moms driving from supermarkets to local CSAs to local farmers markets may result in a huge carbon footprint (per dollar spent on food).

Thus, the food-miles argument just isn’t logical.

Second, empirical studies measuring the carbon footpring of food has confirmed that local foods may or may not have a smaller carbon footprint than non-local food. It is for these reasons that you rarely hear people advocating for local foods based on the idea of food-miles anymore.

It is currently impossible to state categorically whether or not local food systems emit fewer [greenhouse gasses] than non-local food systems.

—

Edwards, Jones, G., L. Mila` i Canals, N. Hounsome, M. Truninger, G. Koerber, B. Hounsome,P. Cross, E.H. York, A. Hospido, K. Plassmann, I.M. Harris, R.T. Edwards, G.A.S. Day, A.D. Tomos, S.J. Cowell and D.L. Jones. 2008. “Testing the Assertion That ‘Local Food is Best’: The Challenges of an Evidence Based Approach.” Trends in Food Science and Technology. 19:265-274.

References

(B1) Brandt, K., C. Leifert, R. Sanderson, and C.J. Seal. 2011. “Agroecosystem management and nutritional quality of plant foods: The case of organic fruits and vegetables.” Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences. 30:1-2:177-197, DOI: 10.1080/07352689.2011.554417.

(D1) Dangour, Alan D, Sakhi K. Dodhia, Arabella Hayter, Elizabeth Allen, Karen Lock, and Ricardo Uauy. 2009. “Nutritional quality of organic foods: a systematic review.” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. DOI: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28041.

(L1) Lusk, Jayson L. and F. Bailey Norwood. “The Locavore's Dilemma: Why Pineapples Shouldn't be Grown in North Dakota.” Library of Economics and Liberty. www.econlib.org. January 3, 2011.

(N1) Norwood, F. Bailey, Michelle Calvo, Sarah Lancaster, and Pascal Oltenacu. In Press. Agricultural Controversies: What Everyone Needs To Know. Oxford University Press: NY, NY.

(M1) McKenzie, Jewel. Alberto B. Manalo. Nada Haddad. Michael R. Sciabarrasi. 2013. Farmers Market Consumers in Rockingham and Strafford Counties, New Hampshire. University of New Hampshire Cooperative Extension.

(P1) Paynter, Henry M. Professor Emeritus of Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The First Patent. Accessed April 14, 2014 at http://www.me.utexas.edu/~longoria/paynter/hmp/The_First_Patent.html.

(W1) Winter, Carl K. and Sarah F. Davis. 2006. “Organic Foods.” Journal of Food Science. 71(9). DOI: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2006.00196.x

References

Lusk, Jayson L. 2013. The Food Police. Crown Forum: NY, NY.

Norwood, F. Bailey, Michelle S. Calvo, Sarah Lancaster, and Pascal A. Oltenacu. 2014. Agricultural and Food Controversies: What Everyone Needs to Know Oxford University Press: NY, NY.