Americans are conflicted about how they believe animals should be raised. Most grocery stores sell both cage and cage-free eggs, and but only 5% of sales are of the cage-free variety. Yet when people are asked to vote on whether to ban cage egg production, as in California, they approve the ban.

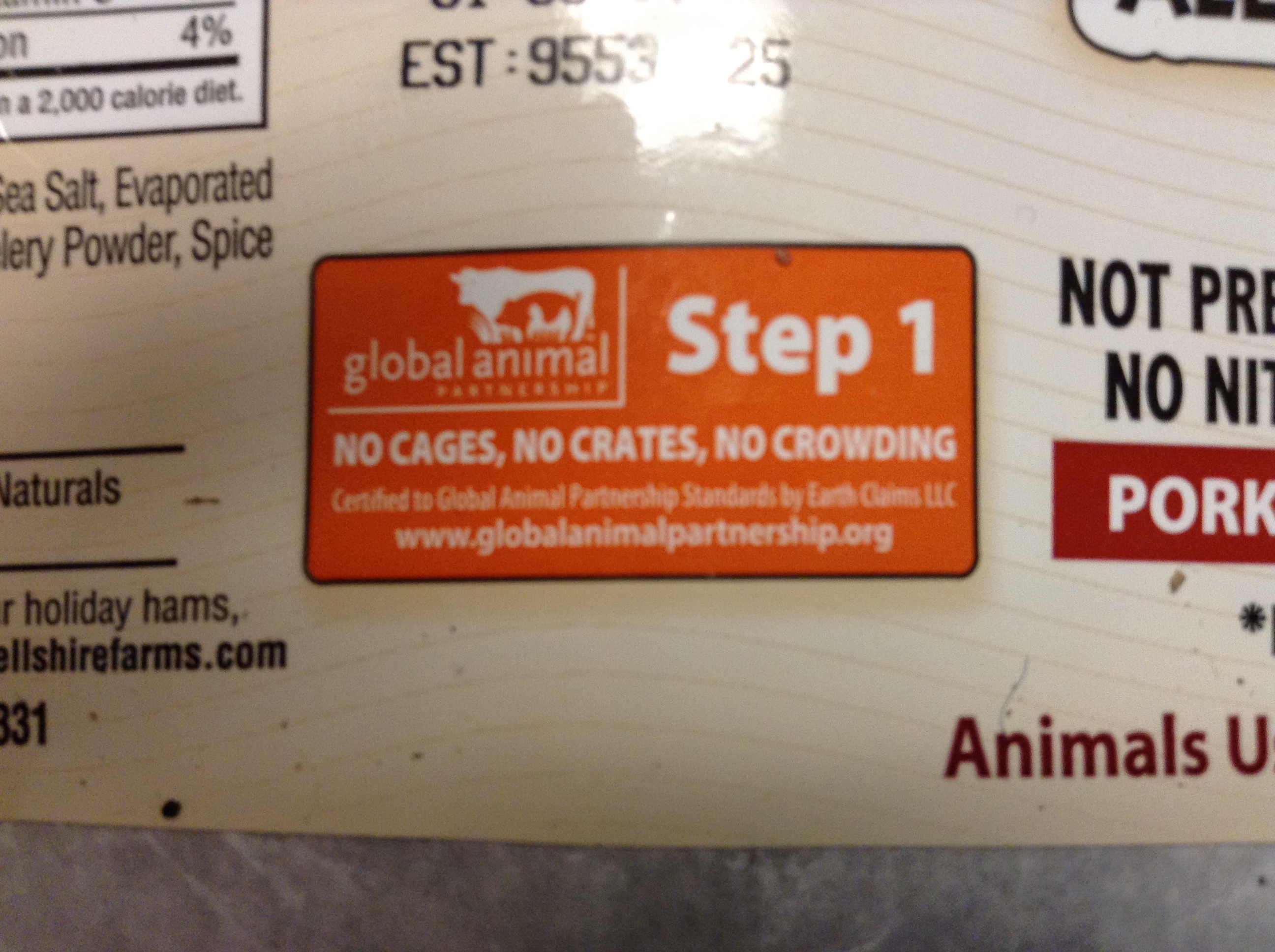

Similarly, in my research consumers tell me they don’t like the stalls used to house pregnant sows, and when given the opportunity ban it in a voter initiative, the ban is always approved. Yet it is almost impossible to find pork advertised as being produced without the stalls. If consumers were really willing to pay the cost of crate-free pork then we would expect pork producers meet that demand. s with eggs, it seems like consumers say one thing when they vote but something else when they shop.

Part of my research involves performing scientific experiments to determine consumers' willingness-to-pay for cage-free eggs and crate-free pork. After designing scientifically controlled experiments and spending thousands of dollars in grant money the data say most consumers are indeed willing to pay more than the additional price necessary for farmers to sell the products. Again, what gives?

Perhaps this is because the average person doesn’t understand the animal welfare issues well, and when they are in the voting booth or my experiments they are thinking mostly about the animals' welfare while in the grocery store they are thinking mostly about their budget. I doubt that animal welfare considerations even register in the mind of most consumers in the grocery store. However, when they vote on an animal welfare issue or participate in my experiments an external force is making them consider it. Consider it, they should, even in the grocery store, because farmers are placed between a rock and a hard place. One the one hand voters tell them to raise animals differently, but if they do, those same voters won’t pay the higher price the farmer needs to raise them differently. Farmers cannot fulfil consumer demand for food until we make our mind up about what we want.

A hog’s life: confinement-crate system

FARROWING ROOM. You are born a female piglet, along with eleven siblings. Because you are born in a barn where humans have easy-access to your mother, you might be born into the hands of a farm worker who cleaned you off, made sure you were healthy, placed you under a heat lamp, and then tended to your siblings. Unlike humans, you can walk almost as soon as you are born, and soon you find your way to your mother’teat, and you begin nursing. Soon you learn that you can approach the heat lamp when you are cold and leave the lamp when you are hot.

Figure dd—

Almost every time you want to nurse, you can, for your mother is confined to a crate slightly bigger than herself. She cannot leave. She cannot even turn around. Much of the time she is lying down. Even if your mother doesn’t want to nurse you, she must. Some mothers abandon their young, but she cannot. A few even cannibalize her young, but even if she wanted to it would be hard for her to get to you unless you just happened to wander close to her mouth.

Figure dd—

Most of the advantages of being raised in a confinement-crate system you will never notice. Because the building will always be at a comfortable temperature. You know neither cold, nor hot. Neither the cold rain, nor the hot humidity of July. Were it not for the gestation-crate, which forces the mother to lie down slowly, you are likely to experience the fear of almost being—or actually being—crushed by her large body.

Because of your excellent health you are unlikely to experience the misery of poor health. The slatted floors underneath your family allows feces to drop below, preventing spread of sickness from one sow to another. Although the floors are hard, there is a soft mat near the heat lamp. At first you have everything you could want. As you grow older though you desire to explore, dig, and play, but there isn’much to do in the confinement-crate system. There is no bedding in which to dig, no new areas to explore. The only real want you have, then is relief from boredom.

Only a few times are you not bored, and they are frightening and painful events. Your needle-teeth may be cut with no anaesthetic, and though you experience the pain, it keeps you from hurting your mother’udder while you nurse, and it keeps you from injuring your siblings if you playfully bite them. Being a female, you need not worry about castration, but your brothers do, and they will have their testes cutoff with no anaesthetic, but perhaps a shot of antibiotics to prevent infection. The farmer needs to assign you an identification number, and she will do so by cutting notches in your ear in a way that spells out a string of letters. Finally, your tail is docked. It hurts, and it is painful, but is less painful than having other pigs bite your tail in the finishing stage of production (discussed subsequently).

NURSERY. You were not ready to be weaned at three weeks. Under natural conditions you would have been much older, but the sooner you are weaned the sooner your mother can be bred again and give birth to step-siblings. Quickly, you are moved to a building they call the nursery, and are placed in a pen with your siblings and other pigs of a similar age. The building smells different than the farrowing crate. That is because it was completely depopulated of hogs before your arrived ad sanitized thoroughly. Being at a young age, and under the stress of an early weaning, your immune system is vulnerable, yet because of the care taken by the farmer to sanitize the building, and because of the antibiotics in your feed, you are unlikely to experience poor health.

The pen has hard slatted floors, but that is all, except for perhaps a chain which you can bite and pull, or maybe a ball. Although you miss your mother’s milk there is unlimited feed, and you love the way it tastes. As with the farrowing crate, your only lacking need is relief from boredom. There is nothing to do in a small barren pen. Well, there is one thing you miss from the farrowing-crate: a soft mat. Here in the nursery there is nothing comfortable to lie on.

CONCEPTION AND GESTATION

Though nearly a fully-grown pig, you will still be called a gilt until you give birth, thereby earning the label “sow”. You may be bred to a live boar, but it is more likely you will be artificially inseminated, which is the farmer’s way of making sure your offspring have genes for fast growth and high felicity. Because you are the product of such a boar, you will conceive quickly and give birth to a litter of twelve farrows (baby pigs), and conceive again quickly after your first litter is weaned.

Figure dd—

Once you have conceived, you have three months, three weeks, and three days until you give birth, during which you must spend in a gestation-crate. Much of the benefits of the crate go unnoticed. Because you are always in good health, poor health is something you never experience and thus take for granted. Although you are sometimes uncomfortable because there is only a hard, slatted floor beneath your feet, the slats allow the manure from you and the others to fall into a pit below, preventing the spread of disease through fecal contact. Being in an individual crate the farmer can give you the precise nutrients you need, in the amounts appropriate for your size. When younger you were allowed all the food you could eat, but now that you are bigger, it would compromise your health. Also, because you do not eat in a group with other sows your food is not taken by a dominant sow, preventing you from obtaining the food you need, and because you cannot take the food of subordinate pigs, resulting in excessive eating, you are at the perfect weight. Although sores might appear on your skin due to the hard floor, injury from other animals will not happen, no matter how cruel the other sows in the building may be.

The problem you face in the gestation-crate is the same problem you will encounter throughout your life: boredom and hard floors. The crate is barely larger than your body; you cannot even turn around. A step forward or backward is possible, but that is all. Eventually you learned to pass the time by biting the bars and lifting them up and down, or scratching at the hard floor with your feet, but it provides little relief.

Each day of your gestation adds only a little weight, so you do not really notice the changes your body is experiencing until it is close to birthing-time. Before you go into labor, though, your boredom is temporarily relieved as you are taken from your gestation-crate and moved to a farrowing-crate. Everything seems exactly the same, except there are empty spaces between your crate and the next sow's crate (later you will learn that space is for piglets only, and there is a little more leg room when you lie down.

FARROWING.

Like your mother, you give birth to a litter of twelve piglets, and though the labor seemed difficult at first, farm workers soon arrived to help bring your barrows and gilts into the world. You have matured from a gilt into a sow. Although your mobility is just as constrained as you were in the gestation-crate the boredom is not quite as acute because you are feeling new emotions. The feeling of twelve piglets scrambling over each other for a teat was strange at first, but as they helped drain the milk the pressure in your udder was relieved, such that nursing was an enjoyable experience. Standing up and lying down was difficult at first, as you the small crate made you do so carefully, slowly. Again, some of the advantages of the farm system are taken for granted because you do not know what life would be on a different farm system. Namely, at least with this letter, you will not feel an odd, moving lump when you lie, and you will not have to learn later that this lump was one of your offspring that you crushed. In this sense you were lucky though. Even with the crates, about 5% of farrows die from crushing (and another 5% die for other reasons). You take advantage of the greater legroom by resting more, and because you are now eating for 13, you are allowed more feed.

Three weeks pass, and you had become so used to the farrowing-crate that you paid little attention to what was going on around you. Sleeping through the moment the farm workers remove your offspring to take them to the nursery, you awake to find all your farrows gone. A little later the workers then move you from the farrowing-crate and back to the gestation-crate. Four days after weaning you are artificially inseminated again, and after another 3 months, 3 weeks, and 3 days, you will return to the farrowing-crate to have a second litter. Then you have a third litter, and then a fourth. For some reason you do not conceive immediately after the fourth litter, and so the farmer decides it would be more efficient to replace you, an increasingly unproductive sow, with one of your offspring, whose youth allows a quick conception.

Just because you are no longer productive at the farm doesn't mean you do not have value to humans though, as you are finally sold to a slaughtering plant where you meat will be made into ground pork.

FINISHING. Suppose that instead of being reserved for breeding by the farmer, and were fed to be used for your meat only. After being weaned you would still have gone through the nursery stage. After being in the nursery for six weeks—where you have no reached nine weeks of age—you will be sent to the finishing floor, which is actually a building. Led into the barn for the first time and directed to your pen, it will seem nearly identical to the nursery. A hard, slatted floor throughout. A trough with unlimited feed. Hard walls. Perhaps a chain or ball to play with, but nothing more. It differs from the nursery in that it is bigger, and you are with a larger group of hogs.

Figure dd—

Although bored, you are in fine health, for your feed is nutritious, the barn is clean and the low amounts of antibiotics added to your feed help you stay healthy (and grow faster). It is a good thing your tail is docked, or in boredom your pen-mates would always be nibbling your tail out of boredom (and you would be biting the tails of others, for you are bored to).

As you and your pen-mates grow, unless you are sent to bigger pens, you will have less and less space to move around. Just before slaughter your body will take up approximately five square feet of space, but the square feet per pig in your pen is only eight.

Then comes the day after which there will be no more boredom. At almost half-a-year old and 275 lbs, you will be taken from your home and slaughtered for meat, providing about 150 lbs(O1) of retail pork—enough to feed three typical Americans for a whole year.

You are a female pig, referred to as a gilt. If the farmer reserves you for breeding you will leave WHAT HAPPENS HERE ????

A hog’s life: confinement-pen system

Now let us look at the life of the same piglet had it been born into a farm that uses the group-pen system for the gestating phase. Everything else about the farm—the farrowing stage, the nursery stage, and the finishing stage—is identical to the confinement-crate system discussed previously.

Figure dd—

After being artificially inseminated for the first time (something that causes no pain, perhaps slight discomfort at times, by the way) you and four other recently inseminated gilts are placed together in a group-pen. It is not a large pen, about double the area that the gilts’ bodies occupy (20 to 30 square feet per sow). You and your pen-mates have room to walk around, turn around, and socialize. It may or may not occur to you that your pan-mates are of similar size to you, and this the farmer did to prevent the injuries you would have suffered if the farmer placed you in a pen with bigger gilts.

Feeding time is rather frantic, as each gilt attempts to eat her food as quickly as possible, both to keep other gilts from eating their share. At first you do fight a little with your pen-mates. There has to be a pecking order, and it can only be established by tempered violence. Once this order is established, however, the pen is mostly peaceful. The dominant gilt knows she will get her way, so there is no need for her to threaten others, and the subordinate gilts know that as long as they yield to the dominate gilts they will experience no harm.

In good health, you want to exercise and explore, and you find the group-pen frustrating because there is simply nothing to do. It would be nice if you could carve a soft resting place out of bedding, but the only material underneath you is a hard, slatted floor.

The only time life becomes really frustrating is when you are ready to give birth and are placed in a farrowing-crate for the first time. A few times before you had been placed in a crate so small you could not even turn around, but that was only temporary, so that something like artificial insemination could be performed. Furious at first, you begin to see its advantages when you are fed and did not have to be on the lookout for the dominant sow trying to take your food, and after two days you are used to it.

Three weeks after you give birth you will return to the group-pen and begin the reproductive process over again.

IS A CONFINEMENT-PEN SYSTEM MORE HUMANE? If you ask animal scientists their opinions about gestation-crates and group-pens in terms of animal welfare, you may hear a variety of responses. Some, like Dr. Janeen Salak-Johnson of the University of Illinois, are vocal opponents of the group-pen system, or at least, oppose farmers being forced to use group-pens instead of gestation-crates by legislation or voter initiatives. The prestigious Journal of Animal Science published two articles, one using mathematical modeling and the other using expert opinion, showing that group-pens were more humane than gestation-crates. These articles do not seem to have convinced all animal scientists. Most, when I ask them, will not deem one superior to the other, but will instead remark that both have advantages and disadvantages, and that because we can never really know what an animal is thinking, it is impossible to say whether the greater space allotment provided by group-pens outweighs the cost of greater animal injury.(B1,B2,N1,N2)

WHAT WILL IT COST? The group-pen system reduces the number of sows a farmer can house in a barn, and in that regard increases her cost of production. It is possible that the sows may be more productive in the group-pen system, enough to keep the cost of production either the same or lower; this is unlikely, however, for if farmers could reduce their costs by converting to group-pens they would have done so already. If farmers must convert a gestation-crate to a group-pen system that increases their costs even more than a group-pen system built from scratch. My research suggests that the costs of raising live hogs (that is, 275 lb hogs ready for slaughter) in a group-pen system is about 10% greater than that in a gestation-crate system. How that would translate into retail prices will be discussed shortly.(S1)

A pig’life: confinement-enhanced system

BIRTH. When the farmer selected your mother to be bred, and when she chose the boar to breed her to, he was selecting for genes that leads to highly reproductive and fast growing pigs, but also for pigs that would grow to be diligent mothers. This was important, as you were born in a farrowing room where your mother could move freely, turn around, and even leave you. If she didn't want to nurse you, it was likely you would starve. If she wasn’t careful when she laid down she might unintentionally crush you. Lucky for you then, that your mother was indeed loving and careful. Still, you and your eleven siblings stood a 10-15% chance of being crushed. Let us suppose, however, that this didn't happen to you.

Figure dd—

So long as you were healthy and not crushed, your childhood is fantastic. There is a deep layer of straw for you and your siblings (as well as your mother) to rest. The straw bedding also gives you the opportunity to did and explore—an activity you naturally yearn to perform.

You will be spared several surgeries. Because all the pigs on your farm are given ample room and an enriched environment, there is little danger of pigs biting each others tails, so your tail does not need to be docked. Nor will your needle teeth be removed, though this may cause your mother some pain, and if a litter-mate bites you it may hurt considerably. One surgery your brothers will not avoid is castration, however, though if raised in Europe they may be treated with a pharmaceutical that keeps the barrow from maturing fast, something called chemical castration, even though the testes are not actually removed.

While your counterparts in a confinement-crate are weaned at only three weeks, you are allowed to stay with your mother another three weeks. During this time you learn to leave the farrowing room, behave in the presence of sows other than your mother, and play with piglets other than just our litter-mates.

NURSERY. Depending on the farm you are born, you might then enter a nursery similar to that of the confinement-crate system. Or, you might enter something like the finishing stage described below.

FINISHING. In all likelihood, by the time you are 9 weeks old you are weaned, healthy, and independent. Compared to piglets in the confinement-crate system, you are braver, as being weaned at a later date and interacting with other pigs helps to reduce the stress of new situations and makes you more mentally and emotionally resilient. It is now time to really start growing fast, regardless of whether you are going straight to slaughter or breeding first. There will be unlimited feed, but it will not contain low levels of antibiotics like those in a confinement-crate system. Does this impact your health? Probably, especially since the use of bedding instead of slatted floors puts you in greater contact with the feces of other pigs, helping to spread sickness. Then again, since you and the other pigs have more room you are not nose to nose, nose to tail, and that reduces the spread of disease. So would you be healthier in the confinement-crate system with its close quarters, antibiotics, and slatted floors? It is unclear, and probably depends more on the particular farm managers at each facility, rather than the production system employed.

Figure dd—

Supposing you are in good health, there is little doubt that you are happier than you would be in a confinement-crate system. Outdoor access is available to you, and though it is only a fenced-in concrete pad adjacent to the hog barn being able to feel the sunlight and smell different scents carried by the winds relieves boredom. There are things to do in the barn also, as the straw or mulch bedding gives you something to dig and and a material from which you can make comfortable bedding. In fact, there is little else you would want in a life, except access to pasture and perhaps forests to explore.

It is only when provided this outdoor access do you realize the comfort provided to you in the barn. Your farrowing hut and nursery provided heat when it was cold outside and cool air when it was hot, such that you always stayed at a comfortable temperature. Even if the barn was not temperature-controlled the bottom layer of the bedding is composting, and that generates heat from underneath.

Without the antibiotics and because the farmer must select sows for good mothering instead of just high growth rates, you grow slower than your counterparts in the previous farms we discussed. As such, you will be slaughtered at an older age and at a lighter weight.

GESTATION. Should you be one of the females reserved for breeding you gestation stage will not be spent in a gestation-crate but pen with other sows. This isn't like a group-pen, as you have three times the amount of space in addition to straw or mulch as bedding. Ample space allotments means there is little fighting among the sows, perhaps some at feeding. Straw or mulch gives them a medium to dig in and soft bedding.

Figure dd—

IS THE CONFINEMENT-ENHANCED SYSTEM MORE HUMANE? High likely, as it improves upon the gestation-crate system in almost every way. One could argue that the increased mortality rate due to the absence of the gestation-crate reduces welfare, and that is true. It is also possible that if the bedding material is not changed frequently enough hog health may be compromised by frequent contact with hog manure. All things considered, though, according to both animal welfare models and expert opinion, the confinement-enhanced system increases hog welfare overall.(B1,B2)

WHAT IS THE COST? If this system scores so high in animal welfare, you might wonder why all farmers don't use it. The reason is that most of you would not buy the pork! Animal well-being doesn't come cheap. While the confinement-pen system incurs costs about 10% higher than the confinement-crate system, those in the confinement-enhanced system are about 30% higher.(S1)

A pig’s life: shelter-pasture system

BIRTH. In this life, you are born a female piglet into what humans consider “natural” conditions. Instead of being born in a barn you are born in a small farrowing hut just large enough for your mother and your eleven siblings. The hut provides protection from bad weather, but not as much as the barn. You feel the cold in low temperatures and feel the hot humidity if born in the summer. However, the straw or mulch bedding provides some heat as it composts, and in hot weather the farmer provides a wallow (muddy area) for you to to cool yourself off. Being a pig, you cannot sweat, and this is why your mother taught you to cover yourself in mud during hot conditions.

Figure dd—

The mortality rate of your siblings is rather high, and some of this is due to crushing by your mother. There is no farrowing crate to protect you, and in cold weather as your family cuddles close to your mother for warmth, she could crush several of you if she lies down or rolls over too quickly. The rate would have been higher if the farmer had not deliberately selected sows that have the genetic propensity towards good mothering. Because the farmer cannot focus on growth and reproductive rates exclusively when making breeding decisions, you do not grow as fast as your counterparts in a confinement-crate system. Because you do not receive low levels of antibiotics in your feed, this makes your growth rate slower also.

Assuming you are alive and in good health, and assuming good weather, your environment is rich in entertainment. Pastures and small wooden areas are available for you to play, allowing you to dig and explore like your feral counterparts. At an early age you will begin interacting with other sows and other litters, and by the time you are weaned six weeks later you can deal with a changing environment while experiencing little stress. Watch out though, because while you are only a few weeks old you are a prime target for hawks.

NURSERY. About six weeks passes before you are weaned, but by that time you had become accustomed to interacting with pigs other than your mother and litter-mates, and the time you spent exploring new areas has made you brave and adventurous. Your nursery may be a pen in a mostly-enclosed barn, with straw or mulch as bedding and unlimited feed. The days are spent playing with your peers in the bedding and sleeping in soft nests made from the bedding.

Try not to get sick, though, because if the farmer gives you antibiotics he must separate you and sell you at a premium under an animal welfare label. Instead you must be sold as if you were raised in a confinement-crate system. For this reason, the farmer may separate you but not give you any antibiotics, in which case you suffer from poor health. This is true if you had been raised in a confinement-enhanced system, also.

FINISHING. There is little difference between your life in the finishing stag of a shelter-pasture or a confinement-enhanced system, except that in the shelter-enhanced version your outdoor access would not be a concrete pad but pasture and wallows.

Figure dd—

GESTATION. Should the farmer decide to breed you instead of sending you straight to slaughter your life would resemble that in a confinement-enhanced area, except that there would be less space per sow in the barn, but you would have access to an outdoor lot consisting of walloww and pasture. The one stressful part of the day, and that is feeding time. Because you are in a group of sows the farmer will dump feed out at many different locations so that the sows will spread out to eat. Still, the dominate sow will attempt to eat her food quickly and then take the food of others. Being fully-grown hogs the farmer cannot feed you as much as you would like because that would make you obese. So you better eat fast, or be ready to fight, or be willing to give up the last few bites of your daily ration. This is also true for the gestation stage of the confinement-enhanced system.

Figure dd—

IS THE SHELTER-PASTURE MORE HUMANE? It depends largely on the farm manager, and the type of farrowing huts and barns that provide you access to shelter. I once visited a farm that was being sold under an animal-friendly label, and while the pigs were given access to pasture and wallows the floor of their shelter was wet and the temperature was below freezing. So long as their shelters are maintained-well and disease is not spread by defecating and wallowing in the same area as other hogs, then the hogs have most of their biological and behavioral needs met. Under these conditions the shelter-pasture system can have the highest rating of all the aforementioned farm systems, or at least be comparable to the confinement-enhanced system.(B1,B2)

WHAT WILL IT COST? The costs of production in a shelter-pasture system are about 18% higher than that of a confinement-crate system.

Figure dd—

Figure dd—

Figure dd—

References

(B1) Bracke, M. B. M., Metz, J. H. M., Spruijt, B. M., & Schouten, W. G. P. 2002a. “Decision support system for overall welfare assessment in pregnant sows A: Model structure and weighting procedure.” Journal of Animal Science. 80:1819–1834.

(B2) Bracke, M. B. M., Metz, J. H. M., Spruijt, B. M., & Schouten, W. G. P. 2002b. “Decision support system for overall welfare assessment in pregnant sows B: Validation by expert opinion.” Journal of Animal Science. 80:1835–1845.

(N1) Norwood, F. Bailey and Jayson L. Lusk. 2011. Compassion, by the Pound. Oxford Publishing: NY, NY.

(N2) Norwood, F. Bailey, Michelle Calvo, Sarah Lancaster, and Pascal Oltenacu. 2014. Agricultural and Food Controversies. Oxford Publishing: NY, NY.

(O1) Oklahoma Department of Agriculture, Food, & Forestry. How much meat?. Meat Safety Division. Accessed February 15, 2014 at http://www.ok.gov/~okag/food/fs-hogweight.pdf

(S1) Seibert, Lacey and F. Bailey Norwood. 2011. ’Production Costs and Animal Welfare for Four Stylized Hog Production Systems.” Journal of Animal and Applied Economics. 14(1):1-17.